🎓 Between Mobility and Marriage: The Unsettling Lives of Chinese Graduate Women Abroad 🎓 在婚姻与流动之间:中国留学女研究生的不安定人生

🎓 Between Mobility and Marriage: The Unsettling Lives of Chinese Graduate Women Abroad 🎓 在婚姻与流动之间:中国留学女研究生的不安定人生

In a compelling talk by Professor Fran Martin (School of Culture & Communication, The University of Melbourne), hosted by the Asia Research Institute (ARI) at the National University of Singapore, a poignant reality of today’s global Chinese graduate women was brought to light: the inner conflict between stability through settling down and the freedom that flexibility and mobility in work and lifestyle can offer.

在新加坡国立大学(NUS)亚洲研究院(ARI)举办的一场讲座中,来自澳大利亚墨尔本大学文化与传播学院的Fran Martin 教授,揭示了一个日益凸显的现象:中国留学女研究生在**“安定”与“流动”**之间所经历的内心拉扯与社会矛盾。

While graduate women are institutionally recognized for their credentials, their stories of ambition, uncertainty, and personal negotiation reflect a deeper societal dialogue: What does it mean to settle?

尽管研究生女性因其学历常常获得体制性的认可,但她们对生活方式、婚姻选择与自我实现的挣扎,反映了一个更深层的问题:

什么才是真正的“安定”?

🔍 The Unsettled Nature of “Settling Down”

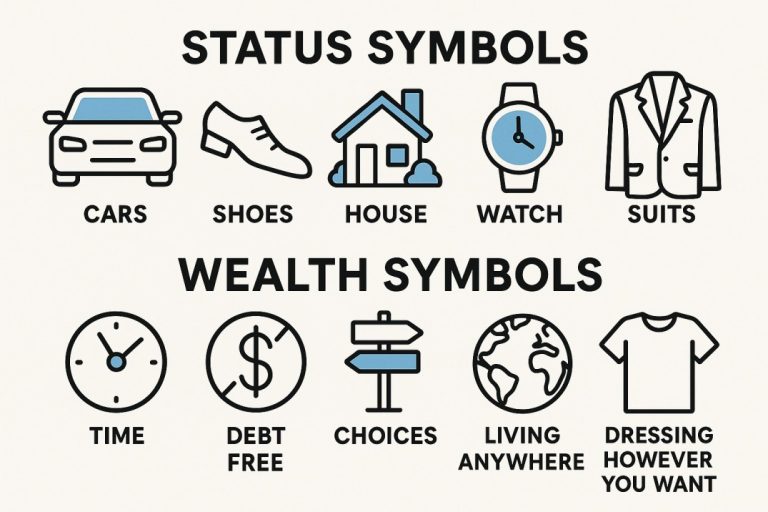

For many Chinese women abroad, “settling down” no longer simply means starting a family. It has become a complex decision-making process, involving the trade-offs between:

- 💼 Career aspirations and job mobility

- 💍 Marriage and societal expectations

- 🧳 Geographic relocation vs. homebound responsibility

- 💡 Recognition vs. restriction

Women with university degrees often benefit from institutional validation (such as scholarships, international credentials, or organizational networks), which opens doors to explore the world, build global careers, and delay or reframe traditional timelines like marriage and childbearing.

🔍 “安定下来”的复杂含义

对于许多中国留学女性来说,“安定”不再等同于组建家庭。这变成了一种需权衡多方利弊的决定过程:

- 💼 职业抱负与工作流动性的取舍

- 💍 婚姻的期待与社会压力

- 🧳 地理迁移与家庭责任的冲突

- 💡 得到认可或遭受限制的两难

研究生女性通常获得体制的认可(如奖学金、学历背景、跨国网络),她们有更多机会探索世界、建立国际职业路径,并能重新定义传统婚育时间表。

In contrast, non-graduate women, though often sharing similar dreams of personal freedom and global exposure, face invisible boundaries due to lack of institutional recognition. Their options are more often influenced by family pressure, economic dependency, or community expectations, which limit their imagination and reinforce the default role of domesticity.

相对地,非研究生女性虽然也有对自由与见世面的渴望,但由于缺乏体制性背书,往往被无形的边界所限制,如家庭压力、经济依附与社区舆论等,这些都限制了她们对人生可能性的想象,并将她们更容易推向“家庭主妇”的角色。

🏛 Historical Context: Equality, Progress, and the Motherhood Paradox

Women’s Suffrage — the legal right to vote — was secured in China in 1949, the same year the People’s Republic of China was founded. In the U.S., the 19th Amendment granting women’s suffrage was passed in 1920. Since then, global movements for gender equality have progressed.

Economically, John D. Rockefeller’s vision of integrating women into the labor force (especially during wartime and post-industrial economies) helped fuel productivity and prosperity. Over time, this strategy normalized women working in all sectors.

Yet despite this progress, biological reproduction still ties women to childbearing, creating the so-called “motherhood penalty.” As a result, women often bear the double burden of caregiving and professional performance, while men — due to tradition or structural advantage — continue to dominate leadership roles.

🏛 历史视角:平权进展与母职悖论

中国女性在1949年获得选举权,与新中国的成立同步;美国则于1920年通过第十九条修正案,实现女性参政权。从那时起,全球性别平等的运动不断推进。

经济上,洛克菲勒基金会推动女性加入劳动力市场,以刺激战争与战后经济发展。这一策略最终让“女性工作”成为常态。

但至今,生育能力仍将女性与“母职”绑定,形成所谓的**“母职惩罚”。许多女性要同时承担照顾家庭与职业绩效**的双重负担,而男性则因传统或结构优势,仍主导社会话语权与高层岗位。

🧭 Rethinking Recognition & Aspiration

Professor Martin’s research highlights that settling is not always a choice, but often a circumstantial compromise. Some women long for stability but feel trapped; others embrace flexibility yet yearn for rootedness.

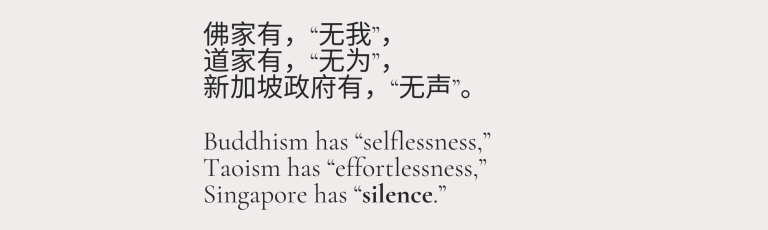

The critical difference lies in how society, family, and institutions recognize their worth. Recognition empowers; its absence restricts.

And so, whether graduate or not, Chinese women across the globe are rewriting the narrative — not simply of marriage or mobility, but of what it means to live freely and fully.

🧭 重新思考“认可”与“志向”

Martin 教授的研究指出,“安定”未必是自主选择,而常常是“情境妥协”。有些女性渴望稳定却被现实困住;有些追求自由却也渴望扎根。

关键区别在于:她们是否被社会、家庭或体制“看见”与“认可”。

被认可,意味着更多选择;

未被认可,则常常只能“适应”。

不论是否拥有学历,遍布世界各地的中国女性都在书写新的生命叙事 —— 不只是婚姻与流动,更是自由与完整的生活选择。

This article is also published on LinkedIn and can be found via this URL.

📚 Further Reading & References

🔹 Women’s Suffrage

- Women in Politics 2019 – Inter-Parliamentary Union: https://www.ipu.org/resources/publications/reports/2019-03/women-in-politics-2019

- UNESCO on Women’s Rights in China: https://en.unesco.org/womeninafrica/china

- U.S. 19th Amendment – National Archives: https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/american_originals/19th.html

🔹 Economic Motives for Women’s Workforce Participation

- Brookings on Women’s Labor Force Rise: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/why-did-womens-labor-force-participation-rise/

- Rockefeller Foundation History – Education & Economy: https://rockfound.rockarch.org/education-and-social-sciences

🔹 Institutional Recognition & Mobility

- Pierre Bourdieu’s Cultural Capital Theory (Stanford Encyclopedia): https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/bourdieu/

- Credentialism and Access to Opportunity (SAGE Journals): https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0038038508096931

🔹 Gendered Migration and Chinese Graduate Women

- Paradise Redefined by Prof. Vanessa Fong (Stanford University Press): https://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=20387

- Marriage and Mobility among Chinese Women (Sociological Perspectives): https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0160597613498311

🔹 Motherhood, Care Work & Gendered Labor Divide

- OECD on Childcare and Women’s Employment: https://www.oecd.org/gender/data/how-does-childcare-affect-women-s-employment.htm

- UN Women – Women and the Future of Work: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/csw61/women-and-the-future-of-work

🎓 This thought-provoking presentation was delivered by Professor Fran Martin School of Culture & Communication, The University of Melbourne 📍Organised by the Asia Research Institute (ARI), National University of Singapore (NUS)